With many organisations and their workforces being able to rapidly adapt to flexible and remote working (coined the greatest work/social experiment of our lifetime), many people are questioning the operating costs and long-term purpose of workplaces: Why do we need a workplace? Do we need all this space? How do we adapt our workplaces and management of them to comply with social distancing? What is the longer term impact on business and people? Will everyone want to work from home?

Based on these questions and taking a cost perspective, many are predicting the end of workplace as we know it without considering the intrinsic role of the workplace to our business effectiveness, society and people.

Our industry and economy is still trying to understand the full impact of COVID-19, and many businesses have gone into survival mode taking precautionary measures to weather the storm. The natural business reaction to the crisis has been to focus on cost reduction and as a result many jobs have been lost, and working hours and salaries reduced.

The outcome is greater uncertainty and insecurity that compounds mental wellbeing for employees.

Now - months on from the initial impact of the pandemic - the spotlight is on the workplace as discussions about returning to the office are at the forefront. Central to these discussions is our established understanding that holistic human wellness is not separate to the workplace.

As much as the recent focus has been on the physical health of people and the need to ‘socially distance’ in order to limit the spread of the virus, there is also a concern for people’s mental health if we do not proactively plan for an effective return and integration into the workplace: Establishing our new way of working.

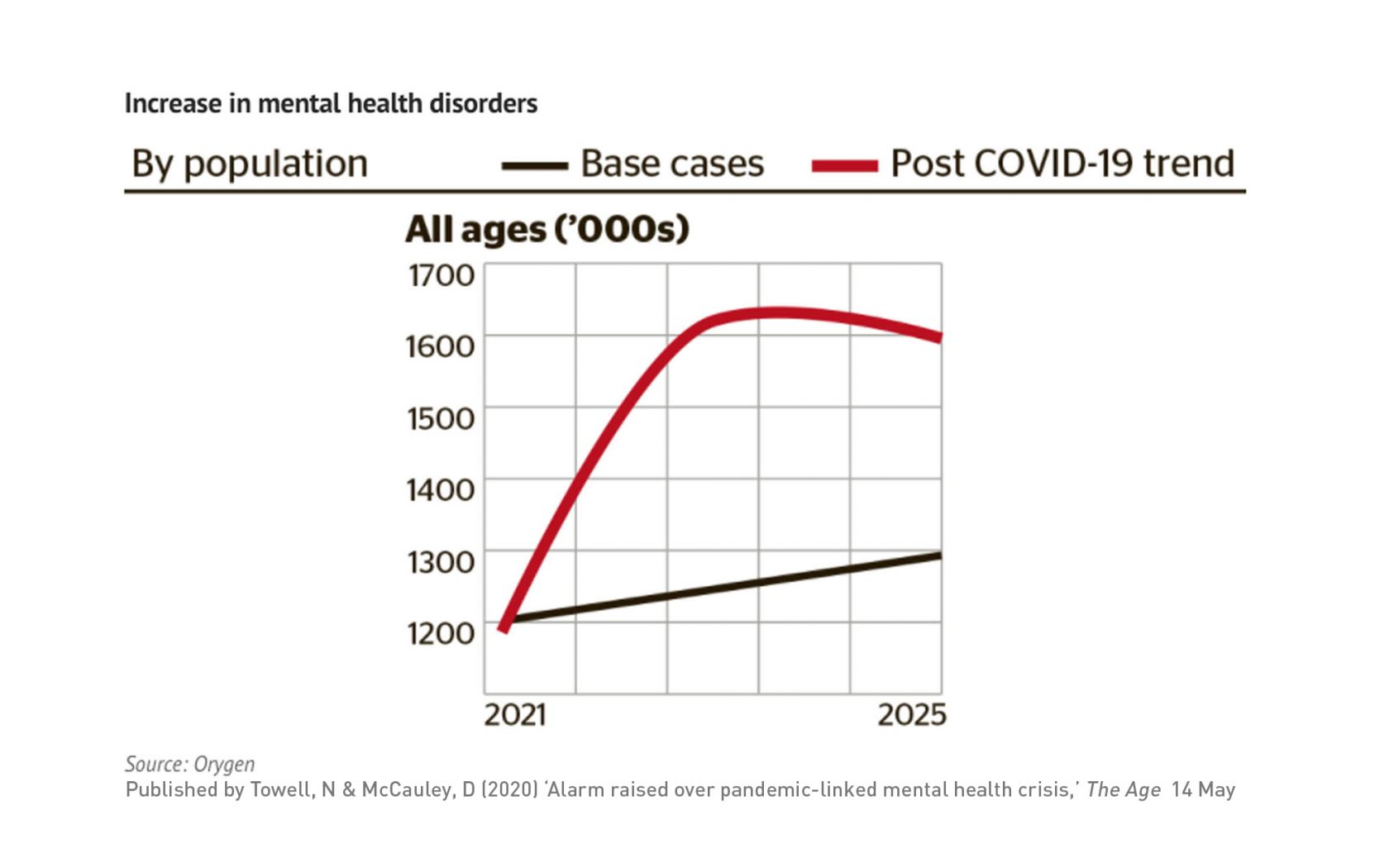

The impact that our time in isolation has had on our wellness has been widely publicised. Whilst some people have thrived, others have struggled and will continue to struggle if we do not realise now the potential longer-term social and financial impact of this pandemic.

Lifeline and Beyond Blue have both experienced an increase in the number of Australians reaching out to them for support since COVID-19 reached our shores.

In addition to this, modelling from the University of Sydney’s Brain and Mind Centre has forecast the financial and psychological toll of COVID-19 could result in an extra 750- 1,500 suicides a year – a predicted 50% increase.

In considering this data, there is an opportunity to look to our workplaces and understand the role that they can play in helping Australians to move forward and ‘recover’.

Watch out for the negative impact of extended working from home

As social beings, humans have an innate need to interact and connect with each other. However, social distancing has resulted in increased feelings of loneliness and isolation for some, as our ability to connect face-to-face has been frozen for an extended period.

With limited access to social support networks individuals are at an increased risk of developing or exacerbating mental health issues. Furthermore, limited social connections, isolation and increased stress can trigger a surge in incidents of domestic violence.

Anecdotal reports from Australia, Brazil, China, and the United States have already indicated an increase in domestic violence.

Another factor threatening our health and wellbeing right now is exhaustion and burnout. Difficulty juggling and separating our professional and personal demands, a forced lack of control over work, an unmanageable workload, and job security concerns have all been recently identified as key drivers of burnout in employees in the wake of COVID-19.

The pandemic has undoubtedly increased the number of hours in our working day, making it even more difficult to balance the pressures of work and home life.

Even before COVID-19, working from home posed potential risks to employees’ physical health due to poor ergonomics and a lack of products that are appropriate for long-term use. As many organisations were forced to react quickly and introduce working from home, the risk of employee injuries due to a poor home work space increased.

For many, the return to the workplace will have a significant, positive impact on their physical health as they will have access to suitable spaces that are designed to support the way that they need to work.

Work relevance and mental health

The latent deprivation theory proposed by Jahoda (1982) states that employment provides five latent benefits that are critical to an individual’s wellbeing. These benefits include participation in a collective purpose, status and identity, social contact, structure to our daily life and activity.

This theory proposes that we all have a fundamental need for contributing to a common purpose where we can feel useful, knowing that we have a recognised place in our broader society, expanding our social networks, structuring our time and being busy or active on a regular basis.

In the recent months, many of us would have experienced insufficient access to, or even a loss of, some or all of these latent benefits due to the changes to our way of working. It is believed that insufficient access to these latent benefits will negatively impact our psychological wellbeing.

Work has been found to be a major determinant of an individual’s identity and mental health. Many people identify work - and the workplace as extension of this - as an important, or even the most important, source of meaning in their lives.

Simply having a place and being employed has been found to be associated with lower levels of depression, high self-esteem and greater life satisfaction.

For employees who believe they are engaged in meaningful work, they are likely to report greater well-being and satisfaction with work and less psychological distress and work-family conflict.

A workplace and our work fulfils our inherent need for purpose and connection and can have a positive impact on an individual’s sense of belonging.

Having a positive sense of community at work can enhance employees’ ability to cope and either decrease or buffer stressful work demands that they may experience. Additionally, employees may establish a stronger self-identity and increased feelings of self-respect as a result of belonging to a team or an organisation.

Finally, feeling a sense of community or belonging at work is intrinsically satisfying, making individuals feel happy and secure with their work and their life.

It is important to note that there is growing evidence of a significant relationship between mental health and employee productivity.

The HERO Study (Goetzel & Ozminkowski, 1998) explored various health risk factors and their associated impacts and found that depression and high levels of stress bear the greatest cost burden to employers.

Evidence shows that employees’ poor mental health has a negative impact on organisations through increased absenteeism, higher human error, and performance and productivity losses. But just as poor mental health can have a negative impact on performance, there is research to show that mental ‘wellness’ can have an equally positive impact on employee productivity.

So before we start saying the workplace is dead, let’s consider how important it is to a business and its people, especially in a time of uncertainty.